I looked at the sky one more time. It was still cloudy. The sun had been playing hide and seek since morning. It rained heavily the night before and we woke up to a misty morning. I hurriedly took breakfast. I was still going through the day’s programme, like I had done countless times, during the night. I rehearsed events and ran my mind through various scenarios. My eyes kept watch over the sky.

I was deep in thought when the persistent naysayer came up with her negative energy again. “Mr. Atemi, what if the chief guest fails to turn up? What will you do?”, I looked at her, shook my head and said; “I am sure he will come. I spoke to him late last night,” I lied. Actually, I had tried calling him several times in vain. My calls went unanswered. At other times, the line was unavailable. I texted him in despair to remind him of the event he was to officially launch. By midmorning, he hadn’t responded to either my calls or texts. But I refused to panic.

“But it is now 2pm and he was supposed to come at 11am?” she persisted. She was an influential member of the board who couldn’t hide her dislike for my closeness to some top leaders in the country. I walked away. She’s the last person I needed near me. Deep inside though I was terrified. If the guest failed to come, it would be a major blow to my departmental performance.

Tension was fast rising. I turned my eyes to the sky once again. Just then, I heard the sound of a helicopter approaching from a distance. I craned my neck and looked through the thick clouds. A dark object broke through the clouds. It came closer. My heart melted with joy. Delighted, I announced to the board members that our guest was about to land. We all hurried towards the helicopter landing bay.

I was delighted as the powerful wind, propelled by the helicopter blades blew the dust, leaves and twigs across the scenic, greenery at the Bogoria Spa. Once the engine had gone silent, the door flung open and out stepped the Chief Guest, Vice President Stephen Kalonzo Musyoka. As we shook hands, he apologised for failing to respond to my calls and texts. He had an extremely busy schedule with President Mwai Kibaki.

I had organised a three-day investment workshop for Kenya’s leading sports personalities in line with President Kibaki’s Vision 2030 and wealth creation programme.

I introduced Kalonzo to the board and management team before proceeding to the hotel lounge for refreshments and briefing.

President Kibaki had introduced fresh rules to the operations of the civil service to improve service delivery. Through, Performance Contracting, each government ministry, agency and parastatal, had to put in place measurable programmes with clear goals and deliverables. As the Public Relations Manager, my department organised a series of events to promote the National Social Security Fund (NSSF) voluntary scheme to encourage Kenyans in the informal sector and the self-employed, to save with NSSF for their retirement.

I entered into partnership with legendary athlete, the six-time World Cross Country Champion, Paul Tergat, to sponsor a series of road races in the North Rift. The 2008 Bogoria Spa event was a culmination of years of sponsorship of young men and women who were intent on becoming world and Olympic Champions.

It assembled past Olympic, World and Commonwealth Gold and Silver medalists. We also had the national rugby sevens team, the national women volleyball team and the national Karate team in attendance. Recently, while scrolling through the event photos, I realised that among my “trainees and Talent Search members”, was the GOAT, marathoner Eliud Kipchoge, then a shy and timid looking youngster.

For two days, we took the sports personalities through the importance of saving for their retirement. We reminded them that the career of sports men and women was extremely brief. On the final day, Kalonzo and Tergat led participants in registering as voluntary NSSF contributors. Tergat put in Sh1 million and many others followed suit.

The workshop was also meant to bring harmony and promote peace through sports. Just the previous year, Kenya had plunged into deep, bloody violence after the disputed 2007 presidential poll. Some athletes in the Rift Valley were caught up in the violence.

Lucas Sang, a middle-distance runner who participated in the 1988 Seoul Olympics and 1992 Barcelona Olympics, was stoned to death in Eldoret town. He was hit on the head with a rock hurled by a gang that ended up setting his body ablaze. Sang’s close friend told Reuters in January 2008 that: “It was at night, in the dark. Tensions were high. They mistook him for someone else, I guess. No one would have done this if they knew it was him. He was so respected”

The late Sang was also Tergat’s friend. Apart from talent searching and promotion, the road races we organised with Tergat also preached peace. It is the ugly violence that threw Kenya into a grand coalition government that saw Kalonzo appointed Kenya’s 10th Vice President and Raila Prime Minister.

I joined the NSSF in 2004 just when Kibaki was settling into the seat of power. He was determined to tackle and slay the monster of corruption that had eaten deep into the fabric of the Kenyan society. He appointed a young and enthusiastic anti-corruption crusader from the human rights movement. John Githongo, became the Tzar to weed out corruption. He had the zeal, the drive and the passion. What Githongo didn’t know is that when Kenya gained independence from the British, some men turned into cockroaches of corruption. They filled every nook and cranny of the nation’s anatomy. With time, some had transformed into voracious rats. By the time Kibaki was being sworn in, many had evolved into vicious snarling hyenas that could kill full grown male lions whenever their eating into public coffers was threatened. They were teeming everywhere. I too met with their agents at the NSSF.

On June 10 2008, President Kibaki launched the Kenya Vision 2030, the country’s development programme from 2008 to 2030. The vision aimed to create a globally competitive and prosperous country with a high quality of life by 2030. It also aimed to transform Kenya into; “a newly industrialising middle income country providing a high quality of life to all its citizens in a clean and secure environment”. The programme rode on the economic, social, political, enabler and macro pillars.

Kibaki also rekindled performance contracting which linked performance to reward for individuals and institutions. It greatly improved public service delivery.

Performance contracting was highly dependent on political will and focused leadership. It encouraged partnership, team work and management and citizen participation. At the NSSF, we prepared quarterly performance reports from departmental to institutional level. This ensured that each and every employee put in their best performance. My department had also prepared the Service Charter for the Fund and the Bogoria event was part of my departmental promise, to promote, brand and grow the Fund.

The Government established Performance Contracting Steering Committee in August 2002. The programme improved efficiency in service delivery, improved performance and efficiency in resource utilisation. It institutionalised performance-oriented culture in the public service. It had a system of measuring and evaluating performance and linking reward for work to measurable performance.

Although performance contracting had been introduced in Kenya through the Parastatal Reforms Strategy Paper approved in 1991, it is Kibaki’s regime that reignited and rejuvenated it in 2003. It rapidly helped in capacity building and enhanced economic performance.

Before the Bogoria event, my former boss at the Fund Mrs Rachel Lumbasyo, had, using the Performance Contracting template, sealed corruption leakages and loopholes at the Fund. Within one year, she had saved billions of shillings.

When she realised a ‘miracle’ had happened, she instructed that we publish the Fund’s financial status in the local dailies, in line with the Retirement Benefits Authority (RBA) requirements. I advised her against the move: “Madam as soon as we publish, the corruption hyenas will land here,” I said. She ignored my counsel with deadly consequences. On the Friday that the advert appeared, a known figure with a litany of cases on his head paid her a visit. I was in her office when the burly politician came. NSSF had sued him for billions of shillings over incomplete projects. He had also filed a counter suit demanding billions of shillings from NSSF.

“Madam, I am willing to withdraw my case against the NSSF. We can move from court to arbitration.” He already had his plan and calculations worked out on how much money he would give her and key politicians “once the matter had been settled through arbitration.”

Madam Lumbasyo told the shameless man in no uncertain terms that she was not interested in his devious schemes. Trouble then set in. She was hunted and haunted. Fake corruption cases were cooked and baked against her. She was hurriedly smoked out of the Fund. The High Court later cleared her of all charges, but the hyenas had won.

Thieves thrive in disorder and confusion. Performance contracting introduced and enforced order throwing thieves into disarray. But they always had a way of regrouping under the darkness of impunity. After Mrs Lumbasyo was thrown out, Labour Minister John Munyes disbanded the NSSF board. The board, led by Cotu Secretary General Francis Atwoli, stood firm behind Mrs Lumbasyo. The board had fully bought into Kibaki’s economic dream. After months of bruising battles, a new Managing Trustee was appointed. I remember drafting the Employment advert for the MT position from the private wing of Nairobi Hospital where I had been admitted for high blood pressure. I chose to stand with the board.

In September 2009, while at the Nairobi Trade Fair, some of the board members made fun of me. The NSSF stand at the show had performed dismally. Because of internal frustrations and sabotage, the money my department required to prepare the show stand to competitive standards was only released a week to the Fair. Our hasty work couldn’t help much.

“Now that the President is visiting the winning Kenya Ports Authority Stand opposite ours, why don’t you use your alleged connections to bring him over to ours,” one board member told me.

“I will try Sir,” I said and immediately called the head of the Presidential Press Service Isaiah Kabira. I explained to him about the NSSF portfolio, the billions Mrs Lumbasyo had saved and how they could be used in supporting the government’s infrastructure development. He listened keenly. A few minutes later, a section of the president’s security team arrived at our stand. They asked me to close certain doors and ask all non-staff members to leave.

“Who are these men and what is going on?” the teasing board member asked me. With a bright smile, I told him: “Sir, you dared me to bring the President.”

Moments later, Kibaki was at our door. He spent quite some time listening to our performance. He was very keen on the figures and what they could do to realise his economic dream.

Kibaki had dramatically transformed the civil service. He made it so attractive that it was soon swallowing some of the best brains from the private sector and civil society movement. Improved government services enhanced competitiveness among government ministries and agencies.

Githongo worked with Kibaki between 2002 and 2005. He served as Permanent Secretary in the Office of the President in charge of Governance and Ethics. To entrench the seriousness of his work, Kibaki gave him an office within State House. His mandate was to help fulfil Kibaki’s campaign promise to deal with corruption.

Githongo quickly established a Public Complaints Unit (PCU) to handle difficult and challenging experiences the public had with government ministries and agencies. He handled requests, complaints and cries from citizens. The PCU became so busy, it was eventually transformed into the Ombudsman’s office. Kibaki set out to fight corruption, recognising that leadership choices informed the behaviour of institutions.

“Within a year, I realised that what I had considered a perk was no longer a perk at all. As time passed, I was reminded that while much that was good emanated from this seat of power, often too, a darkness also arose from this place that sprung from the most craven of our desires and our base greed,” Githongo would recollect after Kibaki’s demise.

He went on; “I came to discover that drought was a business opportunity for some, that the reason the caps of policemen were falling in the rain was a contract. Even the sausages, mandazis and bottles of mineral water that were served to us so efficiently could often be a racket.”

Kibaki was laid back and non-confrontational but a great performer. Within months of taking office, Kibaki, who had inherited a sickly economy, turned it around. Kenya was once more open to business. He made Kenya a viable local and international business destination.

Githongo says that the entire time he worked with Kibaki, he never bumped into people visiting him for tax waivers, which has been an endemic problem with other Kenyan administrations. He says that Kibaki genuinely wanted to fight corruption especially at the beginning of his presidency. However, the NARC coalition partners he had betrayed complicated the equation.

“As Anglo-Leasing rolled on, it became clear that there were dead rats on the rafters of our government hut, - it stank, we knew it was there, we pretended to search for it but understood that the dead rat was very much our own,” says Githongo

Githongo says that: “Mwai Kibaki was a man of a few words. Dunderheads bored him unless they were sincerely amusing. He avoided confrontation at all costs. It wasn’t in his DNA. This means that he spoke in a kind of code even when unhappy with someone or something. And silence was very much one of Kibaki’s languages.”

He says that Kibaki had absolutely no interest in sycophants bringing him rumours and tittle tattle about political schemes of others.

However, it is Kibaki’s strength and weakness that destroyed his legacy. He had too much trust in his old friends. Men he had known from his days in Makerere University. Business partners and colleagues in his golf circles and private member clubs. Some of these men had morphed from roaches to rats and now hyenas. They were the master cartels. These leaders from the Mount Kenya region, The Mount Kenya Mafia, closed in on Kibaki blurring his vision. Soon, they were consumed with the desire to keep power in Kikuyuland.

Kibaki lost the 2005 constitutional referendum leading the country into the 2007 election under the old constitution with disastrous consequences. Even his predecessor Daniel Arap Moi had said the old constitution needed to be reviewed. It is this Kikuyunisation of his leadership and the 2007/2008 post-election violence that Githongo says “culminated in the most devastating part of his legacy; the relatively brief but deadly explosion of violence that irrevocably stained his record even more than losing his grip on graft did.”

Githongo says in The Elephant that: “Witnessing his frailty; Kibaki’s most steadfast allies made up their mind; “Time may be short! Let’s make hay while the sun shines!” Kibaki became a commercial vehicle for a range of actors determined to line their pockets.”

Those close to him say that Kibaki was impossible to hate. He rarely gave one a chance to hate him. He was easy going and, according to Githongo, an effortlessly brilliant interlocutor. He was also a political heart breaker. He betrayed many, among them, former Kitui Senator David Musila who was betrayed twice. Kibaki could smoothly move through the political traffic jam, then suddenly drop off those who trusted him and abandon them at the red lights.

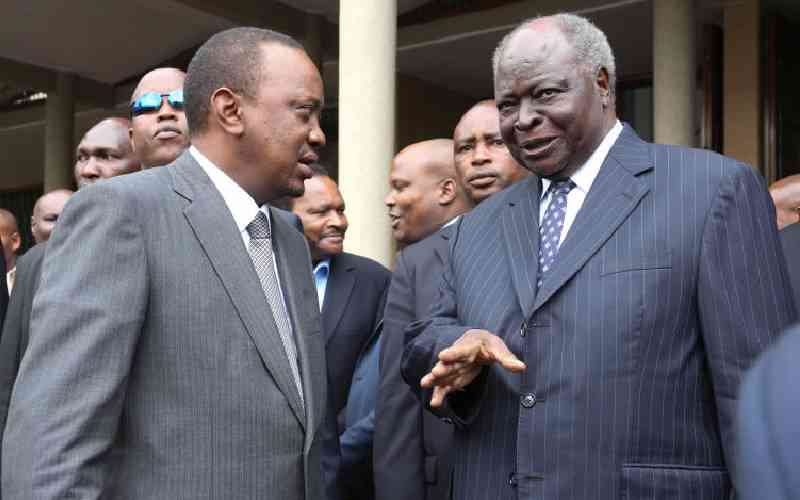

Economically, as soon as he took over in 2002, Kibaki avoided the World Bank and the IMF. He opted for the no strings attached infrastructure from China. He instilled a sense of pride and autonomy in Kenya. Uhuru Kenyatta rapidly destroyed, almost in a flash everything good Kibaki had done.

Writer Rasna Wara says in an article published in The Elephant that: “Uhuru and his inept cronies, have gone on a loan fishing expedition, including massive Eurobond worth Sh692 billion (nearly $7 billion), which means that every Kenyan today has a debt of Sh137,000, more than three times what it was eight years ago when the Jubilee government came to power.”

By 2020, Kenya’s debt stood at nearly 70 per cent of the GDP, up from 50 per cent at the end of 2015. Such high level of debt, warns Rasna, can prove deadly to Kenya because it borrows in foreign currency.

During his 2022 presidential campaign, Deputy President William Ruto embarked on what Githongo calls; “hallucinogenic attempt to distance himself from corruption.” It is this same attempt that Raila Odinga is trying to pull on Kenyans. Both Raila and Ruto, served in the Moi, Kibaki and Uhuru governments. They both owe Kenyan’s some respect by actualising economic lessons learned from Mwai Kibaki.