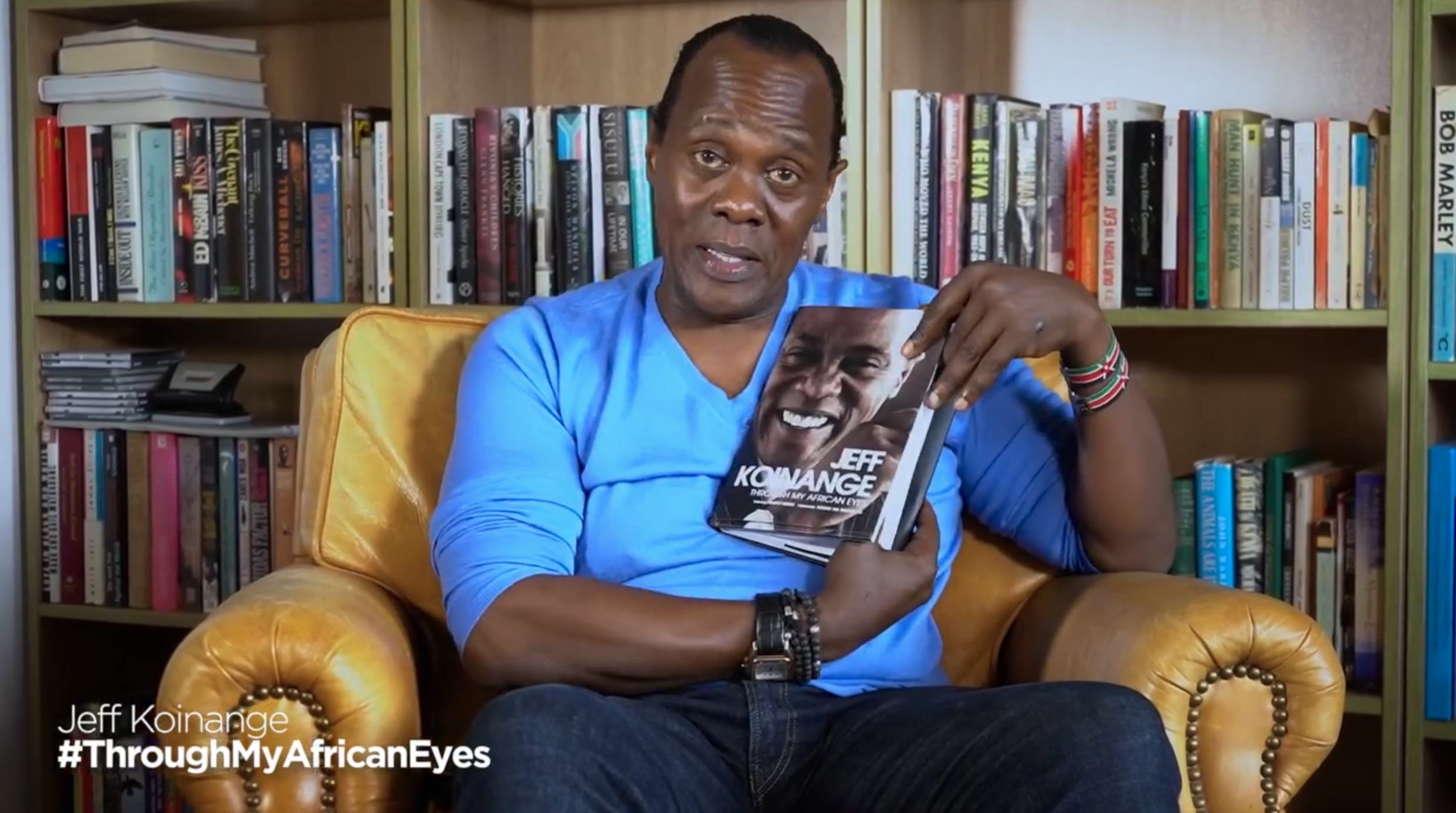

In a recent episode of his series “A Chapter a Day,” renowned journalist Jeff Koinange revisited pivotal moments from his career, sharing insights from his book, Through My African Eyes.

As he delved into Chapter 10, Koinange recounted his transformative journey from Reuters to CNN, highlighting the complex realities he faced while covering the tumultuous Niger Delta.

The Transition to CNN

Koinange’s career took a decisive turn in 2001 when he was approached by CNN’s senior vice president, Chris Kramer, at the Multi Choice African Journalist of the Year Awards in Johannesburg. Initially hesitant to leave the vibrant media landscape of South Africa for the uncertain waters of Nigeria, Koinange was convinced after a visit to CNN’s headquarters in Atlanta.

This encounter ignited his ambition and solidified his place in global journalism.

The Niger Delta: A Dangerous Assignment

Koinange's most controversial assignment emerged from the heart of Nigeria, a region plagued by violence and economic strife due to its oil wealth. He was granted exclusive access to the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND), a group notorious for kidnapping foreign oil workers and engaging in militant activities.

Koinange described the terrifying experience of being caught in gunfire while approaching these rebels, emphasizing the stark realities faced by journalists in conflict zones.

His courage paid off as he captured compelling footage that highlighted the plight of foreign hostages and the rebels' grievances against the Nigerian government.

This reporting not only exposed the dire situation in the Niger Delta but also raised crucial questions about the treatment of hostages and the complexities of Nigerian politics.

Aftermath and Impact

The broadcast of Koinange's report sent shockwaves through Nigeria and beyond. The Nigerian government, caught off guard, initially attempted to discredit the report, claiming it was staged.

However, within 48 hours, all 24 Filipino hostages were released unharmed, proving the authenticity of Koinange's findings.

Reflecting on the aftermath, Koinange expressed pride in his team’s work, stating they adhered to journalistic integrity. The Niger Delta conflict ultimately paved the way for peace negotiations between MEND and the Nigerian government, a crucial step toward resolving long-standing issues in the region.

A Call for Authentic Narratives

Koinange concluded his episode with a powerful reminder of the importance of authentic storytelling. He emphasized that Africa’s narratives must be told from an African perspective, asserting, “If we don’t tell our stories, someone else will.”

His journey illustrates the critical role journalists play in shaping the world's understanding of Africa, emphasizing that these stories are best told by those who live them.

As Koinange continues to share his experiences, he invites feedback and engagement, fostering a community where conversations about Africa’s realities can thrive. Through his lens, we are reminded of the resilience, complexity, and vibrancy of the continent.

Full Transcript:

Hey guys, welcome back to a chapter a day. I hope you've been enjoying my journey of discovery through my African eyes. The book I wrote about five years ago has been published about five years. It's available in local bookstores. I recommend prestige bookshop in the CBD called Ahmed. I'll go there, see Ahmed and he'll hook you up and you live and deliver.

It's available widely. If you already have your own copy, today, we're going to tackle chapter 10, because the last episode we talked about how I worked for Reuters television. That was the first big outfit I worked for in Africa. And people wonder, how did I get from Reuters to CNN? Let's talk about that.

And also the most controversial story I ever did on CNN. A lot of you know about it's about the Niger Delta. We'll get to that in a moment, but here's how it first started. Let's go back. By the way, keep sending your messages, keep sending your feedback, your questions, and we'll engage. That's what it's all about.

It's a conversation. Let's keep talking, folks, because that's what it's all about. So, here we go. In 2001, I attended a CNN Multi Choice African Journalist of the Year Awards in Johannesburg, South Africa. It was here that I met Chris Kramer. By then, he was CNN's Senior International President, Vice President, rather.

And he approached me and said that CNN was about to open a bureau in Lagos, Nigeria. And he asked if I would be interested. I thought about it for a minute. And just as fast, I declined. I said, how am I going to leave Johannesburg and go to Nigeria? It just doesn't make sense. But Chris was very, very convincing.

He said, look, here's a ticket. Come to Atlanta. Spend a week. If you like it, we can talk. If not, go back to Johannesburg. That's exactly what I did. I landed in Atlanta one bright sunny morning, went to the Omni Hotel, downtown Atlanta, the headquarters of CNN, checked into the hotel, and then a little later went on a tour of CNN headquarters.

And I'm telling you, I've never been so intimidated. The way news is put together. the way they transmitted, the way they have a 24 hour network, eight hours, eight hours, eight hours, all 24 churning day after day after day. It was incredible. And I was like, wow, maybe this is where I belong. So a few days later, I get to meet the big boss.

His name was Eason Jordan. He was the man actually behind CNN's Gulf war coverage. He was from the South. You know, he talked to the drawl easygoing man and we just chatted. He threw a few numbers at me. I threw a few numbers back. We chatted for a few minutes and he said, okay, we're done. Come with me, Jeff.

Let's take a walk. By the way, there were a couple of executives with us as we were talking. So we all got up. We all went for a walk. Walk downstairs in the Omni hotel. To a shoeshine guy, a guy was busy shining shoes. Eason approached him and said, Hey doc. That was his name. Doc. Everyone called him doc. Hey doc, you got a place for four?

Doc said, let me just finish here. Mr. Eason, Mr. Eason, I'll be with you in a moment. So he finished with this guy, finished. We all sat down on nice, comfortable leather back chairs and doc started polishing our shoes. And I was wondering what's, what's going on? So in chapter 10, here's how he goes. Doc is at my shoes.

Now he looks at me and says, Hey man, where are you from? I looked at this guy. I said, all right. I said, Africa. He said, Oh, really? Africa is a big place. Where are you from? I said, Oh, okay. Okay. I'm from Kenya. He said, Oh yeah. Jomo Kenyatta country. I looked at him and I said, Oh my goodness, the shoeshine guy in Atlanta knows and now I'm paying attention.

I'm really alert. So he goes on and on and on and he says, Hey man, why are you here? And then stop me. Stop me right away. He says, I know why you're here. You're here for a job, aren't you? I said, come on doc. Doc, you know, everyone's calling him doc. I call him doc. He says, is it that obvious? He says, come on, I can see man.

I see you. I see you. and he says, don't worry man, you are all right. You're gonna do all right here at CNN. And then he turned to Easton and he winked at him. Easton gave him a high five and he says, I like you, man. He talked, he turned to me. Doc, I like you young man. I think you're gonna fit in just fine.

Just like that. It was done. That was Easton's way. of assuring that he had done the right thing by taking you down to the shoeshine guy, Doc, to get his approval. Approval. Can you imagine? By the way, I would visit Doc. I was there for about a week, 10 days. I would visit Doc almost every day. And we'd chat about Africa.

He says, Oh, I've always wanted to go back to Africa. Oh, if I ever come, you're going to welcome me. I said, Doc, anytime you come to Africa, give me a call, especially Kenya. Give me a call. Fast forward a couple of years later, I was in Atlanta. We'd go back every year. I went back to Atlanta. I went back to the same place and Doc wasn't there.

In fact, there was a woman polishing shoes and I walked up to her and I said, Hey, how you doing? He said, how are you doing? I said, where's doc? She said, doc died a year ago. And I felt so bad. So bad. He had had a heart attack a year, a year before. And this was his wife, actually. taking over his business. But I always, always will remember Doc shining shoes at the Omni in Atlanta.

Now, so we're in Lagos, we settled in July, 2001. It was tough settling into Nigeria because it's a tough place. I mean, Nigeria walks with a swagger and you know, every time Nigeria sneezes, the whole continent catches a cold. That was Nigeria. But I'm telling you, the most incredible people I met were in Nigeria.

From the taxi drivers, to the policemen, to the people in the streets, Nigerians are your friends for life. Not pretend friends. To this day, taxi drivers still call me and say, ah, Oga, Oga, how are you now? Ah, waiting happy, Oga, how are family? Finally, to this day. That's true friendship. Having said that, many of you know this story.

It was headlines for a long, long time. And I tell you, it was the most incredible story I ever did. Forget about Sierra Leone, Liberia and other places that I covered. This one. This was the one. So, chapter 10, page 168. The most controversial story, without a doubt, that I did in Nigeria was when I was granted exclusive access by a group of rebels to spend time with them in the dangerous and volatile Niger Delta.

Now, the rebels called themselves the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta, or MEND. They had carved up an area the size of Massachusetts or Maryland for themselves. in the oil rich delta, kidnapping expatriate oil workers and attacking military outposts with the intention of causing as much havoc and unrest as possible.

The entire area was a no go zone and even the Nigerian military was afraid to venture. The situation became worse in the spring of 2006 with kidnappings and killings of foreign oil workers peaking to an all time high. Now, for more than a year, I had been in communication back and forth with my sources deep in the Niger Delta, trying to get access to do the story.

They hated journalists there, by the way. Each time I tried, I was informed that they were not ready and that I would get my chance when they said, okay. I persevered. One day in February, 2007, my source called and said that I make my way to the town of Wairi where further instructions would be sent. I received the usual permission from Atlanta and was cautioned to be careful.

My cameraman at the time, Nick Olo, a freelance photographer, George Esiri, and I landed in Ari, in Wari rather. And as soon as we checked in the hotel, the phone in my room rang. I see you are here. We depart in the morning. Meet us in the docks at 6am. Click. The next day we were up early and at the docks at the crack of dawn.

Sure enough, six young men appeared and approached us and asked us to accompany them to their boat. I hesitated, insisting that we ride in our own boat, if anything, to maintain a sense of independence in the event that we had to make a quick getaway. The men discussed this new development amongst them.

And in the end they agreed, we rented a boat, loaded our gear, but they insisted. Two of them ride in our boat. The boat sped out into the waters, churning a trail of froth behind. An hour later, we were in the high seas, before turning into one of the many estuaries or creeks that make up the Niger Delta.

Once we entered the creeks, we heard. That's right. We heard the sound of gunfire even before we saw the boats. Bullets started whizzing past us. Choo, choo, choo, choo. I could hear that sound. I was familiar with it. It was the sound of 50 caliber gunfire coming right at us. We screamed, raised our hands, and kept saying, We are journalists!

We are journalists! But they didn't care. They kept firing, choo, choo, choo, choo. I shouted at my guys, George and Nick, to keep filming, keep filming. If any, if we're going to die today, I want to die on camera. Nick, cameraman, gathered the strength and began recording as the boats came closer and closer to us.

George, too, clicked away on his stills camera. Throughout these chaotic scenes, The young men in our boat didn't say a thing, didn't flinch. They just drove their boat straight towards the guys shooting at them. Finally, after what seemed like forever, the shooting stopped as the boats came closer and I could see the firepower on board the vessels.

50 caliber, like I said, mounted machine guns, rocket propelled grenades, a dozen or so men in black t shirts, black pants, and back black balaclavas or ski masks. All of them heavily armed with AK 47s and ammunition strapped across their chests. It was the scariest sight I had ever confronted. Scarier than even the child soldiers of Liberian Sierra Leone.

These men looked like they were about to kill us and dump our bodies into the gloomy waters of the Niger Delta. Nick, my cameraman, continued to film as I continued to shout that we were journalists. One of the masked men demanded to know what we were doing there. I was already shaking like a leaf, but I gathered enough strength to explain that we were granted access to, to the creeks to interview the leader of the movement of the emancipation of the Niger Delta or MEND.

No one invited you here. We don't like journalists. You journalists always report the wrong things, he ranted. I regained my composure and stood my ground. If we don't report your grievances, I said, then how will the world know what you want? He gave me a menacing look, cocked his 50 caliber machine gun, and barked an order.

And I thought at first, that was the end of our lives. Follow us, he said, and sped off, splashing us with the murky creek water. My heart must have been sitting in my mouth, and I asked Nick and George if they were fine. They nodded shakily, and we settled down as the speedboats raced towards the choppy waters, weaving in and out of the creeks and out into the open waters.

I kept saying to myself, even if they drop us off here, I would not know how to get back on shore. A half hour later, we slowed down as we came upon a patch of dry land, literally in the middle of nowhere. The masked men jumped out of their boats and waited as we approached before helping pull our boat to shore.

Nick was filming as I jumped out with a tripod and my notebook. George too was clicking away with his still camera. The men led us further into mangrove swamps as we struggled to keep up. As we approached a clearing inside the mangrove, we could hear chanting and singing. I told Nick to continue filming as we entered a compound.

There before us were about a dozen, if not hundreds of masked men dressed in black t shirts, black trousers, black ski masks, chanting and waving guns, once in a while shooting in the air and then continuing their chanting. As soon as they saw us, they turned their attention to us and began coming forward, chanting, singing loudly.

One of them grabbed my hand and led me further into the compound. That is when we saw a whole line of foreigners, complete in orange overalls, sitting on white plastic chairs in the middle of the compound. They led us straight to them and I motioned to Nick to keep, to keep filming. It turned out that they were Filipino hostages who had been kidnapped from their vessels in the high seas more than a month earlier.

and were being held captive. The chanting and singing suddenly stopped as a lone figure walked toward us. The mass men spotted and let him through. He did not introduce himself, but he was clearly their leader. I am glad you are here, he said. You are welcome. Come and see what we have captured. He confirmed that the foreigners were indeed Filipinos and they had captured them high seas and were holding all 24 of them hostage.

I asked if they had been harmed and he smiled and answered in the negative. He explained that nobody knew their whereabouts or seemed to bother to find out as to, to find out as there was no offer which had been made on their behalf. I asked if I could film and interview them and he simply said, why not?

I also asked to interview him and see, and he said, not in the camp, but he suggested we do it out in the high seas later on.

I quickly asked the Filipino sailors who their leader was and he immediately identified himself. I explained who I was and asked if I could do an interview with him. He agreed. And, surrounded by mean looking masked men with weapons pointed at us, I proceeded to ask him questions about long, how long they had been here, how they were being treated.

Was the Philippine government aware of their kidnapping? Were negotiations taking place for the release? You could tell the captain was scared and nervous with all the guns pointed at us, but he answered each question calmly and softly. I learned that they had been captured more than a month earlier, were being treated well and fed three times a day.

I asked him whether he had been in touch with his family and he said they were not allowed any communication with anyone. Then he said in a voice that was almost breaking, I just want to go home to my family. I miss them very much. He walked back to his seat, sat down and broke down silently. I asked to interview another one of the sailors to get a different perspective.

A middle, a middle aged man was brought forward and repeated much of what his captain had said, but added in the end, quote, please tell the world we are being held here in Nigeria. We have nothing to do with the war here. We are just workers. Now we finished the interviews and filmed some more of the mass men and their hostages.

And I decided to do what we call in journalism, a stand up or peace to camera right in front of these frightful looking masked men with their guns. They did not seem to mind as I said the words in what we call one take. That's how scared I was. And then quickly headed towards the boats where the men rebel leader and his boatload of men were waiting for us.

We sped out into the creeks for about 40 minutes before the leaders signal the boat to slow down and for us to approach, we did so and our boats lined up side by side. And for the first time I noticed something about these masked men on their foreheads were the kinds of Trin were kinds of trinkets and beads as though they were part of their uniform.

I learned later on that these were charms or talismans. meant to ward off evil spirits. Now, Nick, my cameraman had been rolling throughout and George was clicking away. As I began my question, who was meant, what did they want? What was their objective? What if their demands were not met? Were they prepared to die for their cause?

Now, this leader, he called himself Jomo, by the way, he answered each question slowly, methodically, meant he sent, was made up of more than 2000 troops and they were prepared to die for their cause. He also warned all foreigners to leave Nigeria because they were ready to wage a complete war against the Nigerian government.

He admitted that the kidnapping of foreign hostages was the only way to make some income to pay for their so called rebellion. We spoke for several minutes before he suddenly raised his hand and said, Enough. It is dangerous out here. The Nigerian Navy is always on patrol. We must go and you must go. And just like that, the speedboat started, sped off into the distant creeks.

In the meantime, Nick, George and I took a deep breath. None of us spoke for several minutes. We still had our escorts with us and they led us back into the high seas for more than an hour before pointing us in the right direction and then jumped into one boat and disappeared. Once again, we took another breath.

We knew right away that this was a big story, which would no doubt raise all kinds of questions from Abuja to Manila about the hostages. And of course, about the strength of men. I told Nick once in Wari we would need to get to the airport, head to Abuja and try to get a reaction from any number of government officials.

After landing in Wari that afternoon, we got a flight to Abuja, arrived in the early evening, headed to a hotel where I started making frantic calls to the Minister of Information, the Chief of Security, Inspector General of Police, and also the President at Aso Rock. No one would pick my calls. And when I called each respective office, I got the same answer.

There's no one here right now. I'll leave a message. Five days later, we were still sitting there unable to get any reaction. I found out that the president was busy on the campaign trail, trying to drum up support for his candidate in upcoming elections. I called Atlanta for some advice and was told head back to Lagos, fly on to Johannesburg, tell the story as it is.

We left Abuja knowing we had the most explosive story we had ever filmed. But more importantly, there were innocent Filipinos whose lives were at stake and hours and days were ticking by. We landed in Johannesburg a day and a half later and aired the story. The whole world was tuned in to CNN for a story that looked like a script right out of Hollywood.

You can imagine the reaction from the Nigerian administration. They had been literally caught with their pants down in a situation that can only be described as complete embarrassment. There's an expert who said later on they had egg on their faces. The response from the Filipino government too was extreme and they began demanding that the Nigerians release the hostages immediately.

The Nigerians responded on the other hand was, well, rather their response was predictable. discredited the journalist and tried to put up a brave face. They succeeded an information minister who issued a statement stating that the CNN crew had staged managed the entire episode, the entire story. They went ahead and denied that there were any kidnapping of Filipinos in the Niger Delta.

Guess what? 48 hours later, all 24 Filipino hostages have been released unharmed. Taken to Port Harcourt before being put on a charter plane back to Manila. The information minister never spoke after that. Looking back at the Niger Delta story, I could not be more proud and complimentary of my cameraman Niccolo and stills photographer George Asiri.

They had braved the elements and captured the story in only the way that pictures are able to tell a story. Many people ask me if I regret doing that story or if I would do it again differently. What would I do? I said I wouldn't change a thing. What we did was follow every journalistic rule we had all the elements except for the reaction from a government official, which we had tried to do for nearly a week.

The story still stood, and most importantly, it hap, it had a happy ending. For the next, for the hostages, at least by the way, fast forward, a couple of years later, a peace deal was struck between the Nigerian government and mend. Some of them were granted amnesty. A lot more needs to be done in the Niger Delta, but you know what?

At least it was a start. It was a spark that began talks to ease the tensions in the Niger Delta. It was an incredible story, and you can read more of it right here. Through my African eyes. With my journey of discovery. Right here on the African Continent. And there are many, many more stories. Many stories I want to tell you, and I will tell you.

But I ask for your feedback. What do you think? What are your thoughts? What questions? What stories? My background, don't forget. Where did I come from? I'll tell you all that. for listening. In the next episode, keep tuning in at Koinange Jeff, keep spreading the word through my African eyes. We have to tell our stories.

And if we don't tell our stories, someone else will fly from out there, parachute in and tell our stories for us. That's why it's called his story. It's his story. It's not our story. Our stories are best told by us. And my story is right here through my African eyes. See you next time.