In our series of letters from African journalists, media and communication trainer Joseph Warungu reflects on the broken political marriage between the Kenyan president and his deputy, as well as the third person in their troubled relationship.

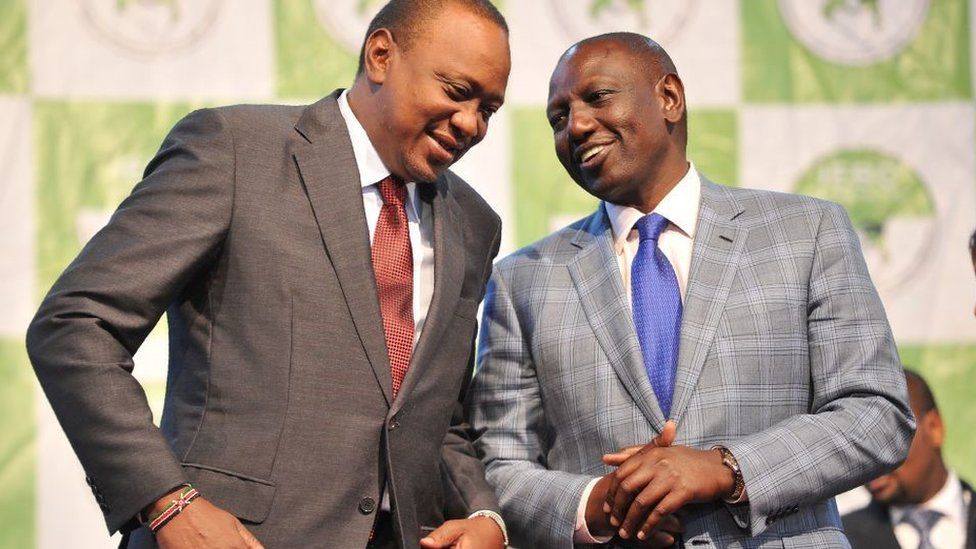

Like any other couple on their wedding day, President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto wore broad smiles when they stood on stage.

Against all odds, their Jubilee coalition had been declared the winner of the presidential election on 9 March 2013.

Ruto called their victory a miracle, saying God had turned insurmountable hurdles into bridges for their coalition.

The marriage was a convenient political move after the International Criminal Court (ICC) tried, in what turned out to be a failed attempt, to put them on trial for the devastating political violence witnessed in Kenya in 2007.

Digital couple

Love was in the air in those early days.

The couple walked together, sometimes hand in hand; and worked in sync, at times dressing alike.

They prayed together in public and they laughed a lot. An excited public laughed with them, too.

Life was good, the marriage was strong and the future looked bright.

Kenyatta was 51 when they first assumed office, while Ruto was 47.

The man they had defeated, former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, was 68 at the time.

He was branded old and of the analogue generation that defined Kenya’s dark and forgettable past, while the new “youthful” presidential couple was defined in modern terms – a digital couple.

Eight years and two presidential elections later, the marriage is broken and we, their children, the ordinary citizens of Kenya, are lost.

The handshake that changed politics

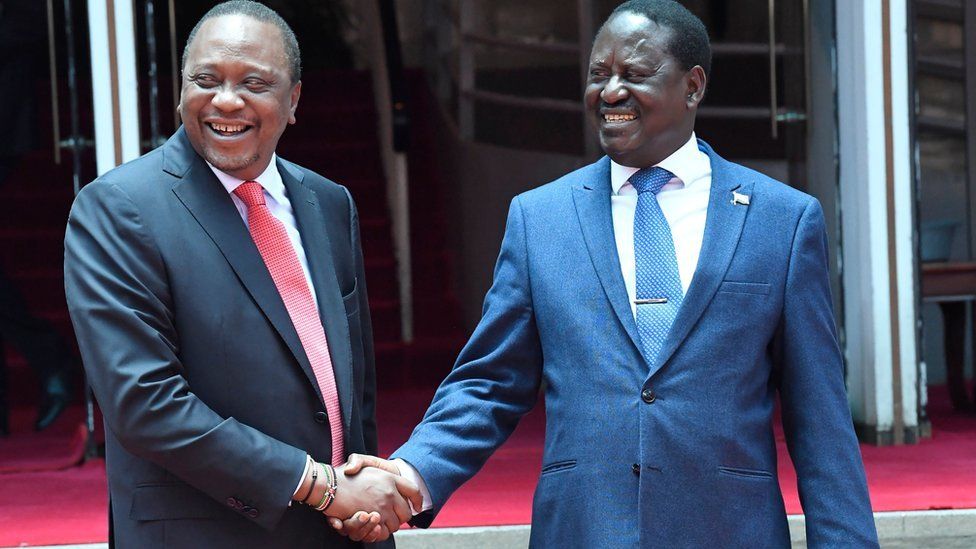

The first sign of the break-up came in March 2018, when the president introduced his old rival, Mr Odinga, as the third partner in the union.

After the 2017 election, Mr Odinga, who was also in a polygamous union in the National Super Alliance (Nasa) with three other partners, had launched a wave of protests complaining that the poll was not free and fair.

Concerned that protests would undermine the delivery of election pledges in his final term in office, President Kenyatta reached out to Mr Odinga and the two men shook hands in public as a declaration of peace.

Slowly, Mr Ruto started drifting away from his partner of five years, complaining the marriage was too crowded.

Today, the strain between the presidential couple is displayed openly.

They avoid one another. Their body language speaks of a cold marriage and a frozen bed.

Ruto refuses to walk out

Mr Odinga has since moved into the matrimonial home, and like younger wives, he seems to attract love and passion from Mr Kenyatta who is never shy to praise him in public.

During the 1 June Independence Day celebrations, the president declared that he had made bigger strides in terms of development during his time with Mr Odinga than with Mr Ruto.

However, a sulking Mr Ruto has refused to resign – or move out of the matrimonial home. He spends his time in the guest room, complaining to anyone who cares to listen that he was abandoned despite having assisted the boss to build the empire.

Geofrey Angote”In Kenya political marriages are hardly based on ideological convergence – they just bring together different ethnic kingpins”Joseph Warungu

Media and communication trainer

Mr Ruto feels betrayed by President Kenyatta, who has not kicked him out because it could make things even messier.

When the two joined forces, they had an unwritten 20-year prenuptial agreement, in which Mr Ruto would back Mr Kenyatta to serve as president for two five-year terms.

After that Mr Kenyatta would reciprocate by supporting his deputy to win the presidency in the 2022 election and he too would serve two terms, totalling 10 years.

But in January 2021 the president gave the clearest declaration yet that the deal was dead.

“The presidency does not belong to only two tribes,” the president told a public gathering, adding that it was perhaps time for another of Kenya’s 42 ethnic groups to take over.

The president noted that only members of two communities have occupied the top seat in Kenya – the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin.

Mr Kenyatta is Kikuyu, Mr Ruto is Kalenjin while Mr Odinga comes from the Luo community, which has long complained about being excluded from power.

In Kenya political marriages are hardly based on ideological convergence – they just bring together different ethnic kingpins whose main interest is state power and an unlimited access to national largesse.

Kenya is broke

Mr Ruto does not buy the argument that the Kalenjin cannot rule again or that he cannot unite, once more, with the elusive Kikuyu.

He’s on the political war path now, with frequent trips to central Kenya to woo the Kikuyu.

He is fighting hard for the matrimonial spoils and wants custody of the children.

And we, the children, are torn in our love for the men.

Do we stick with dad who is supposed to retire from the presidency next year?

Do we embrace his new partner Mr Odinga, who offers a future of peace and a more equal society, blended with uplifting reggae that he occasionally sings on stage when campaigning for changes to the constitution?

Or do we follow Mr Ruto – the ex, who is bold, energetic and promises hope for the masses that are struggling to make a living?

The breakdown of Kenya’s presidential marriage has come at a big cost. The home is broke.

Children in pain

International financial institutions, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), have had to step in with loans to help cover the national budget deficit.

Repayments will hurt. These organisations are demanding a restructuring of expensive publicly funded institutions including some universities and Kenya Airways. This will mean lay-offs.

The price of essentials like fuel, mobile data and cooking gas has shot up.

Divorce is never cheap. It’s painful, stressful and emotionally draining.

While the separating parents are already eyeing other political partners, the children have no other home but Kenya.

There are indications that the general election scheduled for next year could be postponed to accommodate possible constitutional amendments, including increasing the size of the cabinet and creating more parliamentary constituencies.

The destitute children are worried that their pain could be stretched out even further.